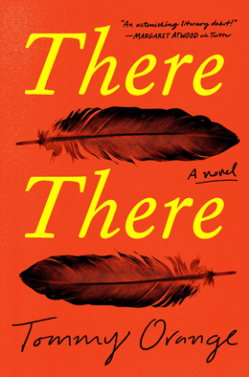

There There follows a large cast of Native American characters, all of whom are determined—for reasons ranging from the artistic to the criminal—to attend to the Big Oakland Powwow, a gathering for Native American people to honor their culture and tradition.

The cast includes: Tony Loneman, Edwin Black, Orvil Red Feather, his estranged grandmother Jaquie Red Feather and her sister, Opal. There’s also Dene Odendene, who’s working on a film project to record people’s stories of what it means to be Native American. Through alternating point-of-view chapters, we follow each of them on their journey to the powwow, both in the literal geographic sense and in the historic sense of how their personal background motivates them go.

There There is a novel about identity—specifically the Native American identity—and how it has been bent in and out of shape by poverty, urban life, segregation and discrimination. It’s also a novel about belonging. As [one of the characters] says at one point: “I feel bad sometimes even saying I’m Native. Mostly I just feel I’m from Oakland.”

Writing these lines, questions come to mind about the relationship between identity and place. How much of our identity do we derive from the place we live in, and how much do we derive from our heritage and the traditions of our ancestors? In this novel, Orange challenges the dichotomies of cultural identity; most of the characters in this novel are native and urban, they are traditional and contemporary.

Stories are always about who we are, where we come from, where are going, and what it all means, and Tommy Orange meditates on all these questions in There There. Like all great literature, There There embeds these universal questions of identity and belonging in the personal stories of its characters, most of whom are Native American. In the prologue, he comments on the experience of Native Americans in the city of Oakland: “Plenty of us came by choice, to start over, or to make money, or for a new experience. Some of us came to cities to escape the reservation. … The quiet of the reservation, the side-of-the-highway towns, rural communities, that kind of silence just makes the sound of your brain on fire that much more pronounced.” Most poignantly, he writes of contemporary Native Americans: “We know the sound of the freeway better than we do rivers,” and yet at the same time, “what we are is what our ancestors did. How they survived. We are the memories we don’t remember, which live in us, which we feel, which make us sing and dance and pray the way we do […]” There is a tension here between modernity and tradition that the characters will contend with throughout the novel.

How can native communities preserve ancient tradition and embrace modernity at the same time? This tension is relevant in any society today. Globally, we are experiencing a mega-trend towards urbanization. The World Bank estimates that over 55 percent of the world’s population already lived in urban areas in 2018 and it expects that this proportion will grow to two-thirds by 2050. We are also seeing international migration as people are either displaced from their homes by war and climate change or choose to emigrate in search of economic betterment. Societies are already asking themselves: who are these people who come from there and are now here? How do Germans treat Syrian refugees? How do Americans treat Central and South American migrants? How will we treat Ukranian refugees? And how will those people evolve their sense of identity, their cultural legacy, as they create a new life in urban or foreign places?

It seems that in this novel, the characters have various ideas of who they are supposed to be (more Indian, more masculine, more outgoing) and they try to act in accordance to those vague and inauthentic conceptions even when they don’t appear to feel comfortable in those categories. The result is suffering, both in the individuals and in their communities.

I’ve explored the relationship between place and identity elsewhere. It’s one that interests me and perhaps that’s why There There is a novel that left me both celebrating and grieving its characters like they were old friends. Tommy Orange’s skill as a writer is clear in the empathy with which he treats every single member of the large cast of characters of There There, regardless of how flawed they appear to us. Discovering how each character is related to another is thrilling. Towards the end, when all their stories come together in the Big Oakland Powwow, the reader can see the whole picture and almost feel part of their group story. All of them will coincide at the powwow and their actions will affect each other in heartbreaking ways that reflect the reality of contemporary life for many marginalized communities.

There there is a very well-crafted debut novel in which Orange introduces us to the complexity of contemporary Indian life in a way that is very relatable for active readers. The narrative demands that we look directly at the history of how colonialists systematically forced Native American tribes out of their land and the identities that were rooted in it. It invites us to ponder on the future of native communities and their culture in an increasingly urbanized world, but also about our own relationship to past and future generations and the responsibility we might have to each. The novel’s ending leaves it up to the reader to imagine whether that future is hopeful or bleak.