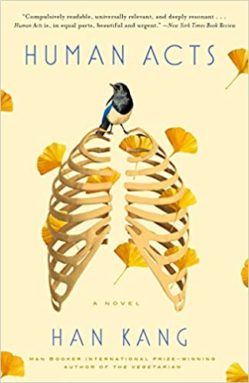

Human Acts, a novel by South Korean writer Han Kang, is a beautifully written story about how the South Korean government’s violent reaction to the pro-democracy uprising in May 1980 in Gwangju impacted individual people’s lives. The novel first introduces us to Dong-ho, a young boy who goes to a school gymnasium, where the corpses of pro-democracy demonstrators killed by government forces are piling up. Dong-ho, who is looking for his best friend’s body, ends up helping clean the bodies so family members can identify them. Later chapters tell us the stories of other victims of the Gwanju uprising who were somehow connected with Dong-ho, either intimately, like his grieving mother and his best friend’s lingering soul, or tenuously, like the women working in the gymnasium, who were later imprisoned and subjected to torture and sexual abuse.

While I was reading Human Acts with a few other friends, one of them confessed that she wouldn’t finish it because it was too graphic. This was interesting to me because this was during the worst of the pandemic in Spain when I actually found myself reading less than usual and rejecting the dramatic television shows I used to follow avidly. It was as if my own experience of the real world was emotional enough without having to take on fictional problems. And when my friend made this comment, I understood that she was having a similar experience while reading Human Acts. She had enough suffering in the real world to accept it in fiction.

And that’s when I realized that it’s in that challenge to turn away from the story that the novel’s power lies.

Han Hang is a writer who does not flinch away from the gruesome, not because she wants to shock us, but because she wants to show the truth. In prose as clean and sharp as broken ice, Han describes a rotting corpse or a torture scene with an accuracy that dares us to look away but doesn’t want us to. It’s as if Han Hang’s characters are asking us: Where will it leave us if you turn away? Who will we be if you flinch?

One of the characters, the editor Kim Eun-sook asks this directly: “what is humanity?” And “what do we have to do to keep humanity as one thing and not another?”

Human Acts suggests that part of the answer is by telling stories. Novels allow us to inhabit another person’s consciousness intimately. The relationship the reader enters with the characters and with the writer is in many ways more intimate than any relationship in the real world. The novel asks us to imagine, even if for a moment, what it’s like—what it’s really like—to be somebody else.

That can be tough when the character is experiencing trauma. Human Acts is the type of novel that confronts us with the worst of what it means to be human. At the same time though, it tells us that it’s precisely by reading these stories, by refusing to shrink away from the unpleasant images of rotting corpses and raped bodies, that we protect our humanity.

This idea might run contrary to the desire for fiction that helps us escape into a reality that seems more desirable than our own. I often feel though that the most powerful stories are also the saddest, the most difficult. Maybe it’s because showing interest in each other’s stories is how we show love and compassion for each other. “Want to talk about it?” we tend to ask friends who are going through something tough. We tend to believe that the very act of telling a story has healing powers.

And yet, some of Kang’s characters are offended when a professor asks them to tell their story. It can be difficult. “You want me to tell you about these dead kids, professor?… What right do you have to demand that of me?” This character does not want to relive the pain she experienced. What good would that do? “Would that bring Jin-su back to life?” he asks. “How could we ever hope to understand what he went through, he himself, alone?”

Of course not, we say. The story will not bring the murdered back to life. And no, most of us cannot hope to understand the pain endured by anyone who has been persecuted or tortured. But a novel like Human Acts shows us that it’s not for our benefit that we hear the story. It’s for the benefit of the teller. By receiving their story and holding it gently, we acknowledge the other person’s right to grieve, to rage, to resist, to survive, to heal.

And yet, the prisoner challenges us again. Furious, he wonders if human beings are fundamentally cruel. “Is the experience of cruelty the only thing we share as a species? Is the dignity that we cling to nothing but self-delusion, masking from ourselves the single truth: that each one of us is capable of being reduced to an insect, a ravening beast, a lump of meat? To be degraded, slaughtered – is this the essential of humankind, one which history has confirmed as inevitable?”

Han Kang seems to say, “no!”. And I agree. The prisoner doesn’t want to tell us his story, but we know that the act of listening to another person’s story of pain is how we keep each other’s dignity alive. The act of listening to another person’s story is an act of recognition of the other person’s value. The very human act of sharing stories, the bright ones, and the horrible ones, is one of our most powerful bulwarks against the terrifying fact that as much as there is love and beauty in humanity, there is also cruelty.

“I never let myself forget that every single person I meet is a member of this human race. And that includes you, professor, listening to this testimony. As it includes myself.”

―

Exchanging stories is a uniquely human act. Our ability to imagine what it would be like to be somebody else and imagine what it might feel like to go through something is unique to our species. And the novel’s hope is this ability can repair the cruelty of those other uniquely human acts described within it. It’s in the title.

As the prisoner reminds us towards the end of Human Acts, “every single person [we] meet is a member of this human race.” We are all alone, every day, each of us facing the fact of our own humanity and knowing “that death is the only way of escaping this fact.” Kang tells us that we, who are all just human, don’t have answers for each other. What she doesn’t say, what she only allows us to experience through her novel, is that how we protect the goodness in humanity is by showing up for each other. By refusing to flinch. By refusing to turn away. By sharing stories, we create those communities.

This is a novel that reminded me of all that. So, go get yourself a copy of Human Acts by Han Kang, and then post your thoughts in the comments.

Discussion questions for Human Acts by Hang Kang:

1. At what points in the narrative did you feel yourself wanting to turn away from the images evoked by the prose? How did you feel reading passages such as this one?

2. Whose story did you feel most drawn into? Why?

3. How can narrative retelling and remembering provide cathartic release from sufferers of trauma? How can it cause more suffering?

4. Thinking of the characters you found most compelling, how do you imagine you would have acted in similar circumstances? What do you think you would have done differently?

5. Why do we observe the funeral ritual when someone dies? How were the characters of the story affected by their inability to have a funeral for their loved one?

6. Do you think humans have a soul?

7. Is it inevitable for humanity to continue committing acts of such cruelty as those described in the novel?

8. How much do you know about the Gwangju uprising in South Korea and its aftermath? Are there similar instances of violence in your own country’s history? What stories have you heard about them?

9. How do you feel about the Gwangju’s students’ acts of protest for democracy? Were they brave? Was their death pointless or did it serve a greater good?

10. What brave human acts have you done recently?